The KSK and its Founders:

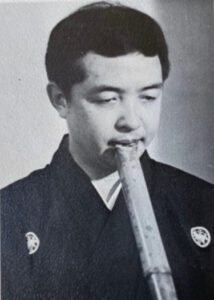

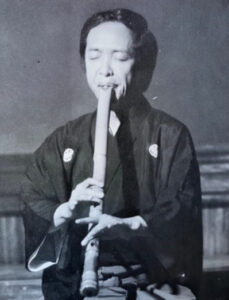

Yokoyama Katsuya (1934 - 2010)

Yokoyama Katsuya was born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1934. Initially named Shin’ya, he was a third generation shakuhachi player in the Yokoyama family.

Yokoyama Katsuya was born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1934. Initially named Shin’ya, he was a third generation shakuhachi player in the Yokoyama family.

His paternal grandfather, Yokoyama Koson, is said to have been a Kinko player in the Kawase line and was possibly a maker of shakuhachi, though it’s unclear whether or not Yokoyama Sensei had any personal memory of his grandfather as either a player or a maker. He knew him rather as an accomplished but somewhat eccentric fisherman who was quite skilled at designing and making his own fishing gear.

By contrast, it is well known that Yokoyama Sensei’s father, Yokoyama Rampo, was quite an accomplished shakuhachi maker and an excellent player. In fact, there are some who hold to the opinion that he may have been one of the best pre-war makers of shakuhachi in Japan during the 1930’s. It appears that he was a Kinko student under his father Koson, prior to becoming a longtime student of the popular composer and founder of the Azuma school of shakuhachi, Fukuda Rando.

Yokoyama Sensei’s mother was also a musician, a koto player from a merchant family that hailed from Shizuoka. It has been suggested that she influenced the trajectory of Yokoyama Sensei’s musical career at a number of key junctures, including his choice of teachers. It was also Mrs. Yokoyama who suggested that her son Shin’ya (whose name meant ‘the honest or faithful one’) adopt the stage name Katsuya. To her it was a much stronger sounding name and she thought the meaning was important for him: the one who wins.

There is no reliable record of how Yokoyama Sensei initially became interested in learning shakuhachi. It seems likely that his first exposure to the instrument and to Honkyoku would have been through his father’s playing, and it may be that playing the flute was an interest and an activity that he just naturally gravitated toward during his upbringing. There is evidence though that as a boy, he was also familiar with and appreciated the playing of Watazumi Dōso – at least to the extent that he allegedly nearly wore out an LP recording of Watazumi’s “San’an” by playing it so often. This is a story that several of his students heard directly from Yokoyama Sensei himself.

While it is clear that Yokoyama Sensei was studying shakuhachi during his high school years, details regarding his early formal training are unclear. He told at least one friend that he began shakuhachi as a student in the Azuma school based on his father’s relationship with Fukuda Rando, the school’s founder as noted above. And to his students, he alluded more than once to his playing habits during high school. We don’t know however how old he actually was when he began formal training. We also don’t know if his father was his first formal teacher or if he trained with a different Sensei in the Azuma lineage.

In any case, he described this exposure to the Azuma tradition as fortuitous and as a good fit for him, probably for several reasons. To begin with, the Azuma tradition allowed for notes to be fingered in a variety of different ways as long as the correct pitch was produced. This flexibility suited Yokoyama’s temperament since it may have promoted a more free approach to performing, in contrast to the more fixed method of the Kinko school. More importantly perhaps, Yokoyama was a fan of the sweet and lyrical laments that Fukuda was famous for composing. He made several recordings of Fukuda’s pieces and often included them in his concert programs. Also, by the time Yokoyama began his brief period of personal study with Fukuda in 1959 – when he was 25 and Fukuda was in his mid-50’s – Fukuda had also become a welcome friend in the Yokoyama household. By all accounts, there was a warm and affable connection between Yokoyama Sensei and Mr. Fukuda based on a shared musical aesthetic but also a genuine friendship.

Yokoyama Sensei’s other formal teacher ended up being Watazumi Dōso, whose music he had admired as a boy. In contrast however to the student-teacher relationship Yokoyama Sensei enjoyed with Fukuda Rando, his relationship with Watazumi was much more complex. And, like much of the mystery and uncertainty that tends to surround Watazumi, there are several different versions of the story as to how Yokoyama Sensei became his student. There is nothing definitive however, and the truth is probably an amalgam of all of these. It’s probably safe to assume that all those childhood hours spent listening to Watazumi’s “San’an” must have had an early and nascent influence on Yokoyama’s eventual playing style. It wasn’t until Yokoyama was 24 however that he finally had the chance to hear a live performance and, by one account, was so moved by the quality and intensity of Watazumi’s sound that he made the decision then to become his student.

As noted above however, there is evidence that Yokoyama’s mother made her own contribution to the process of him becoming Watazumi’s student. Some years ago, she related a story to Mr. Kakizakai that she happened to catch a performance of Watazumi on the radio, was amazed at his playing, and suggested to Yokoyama Rampo (Katsuya’s father) that he invite Watazumi to visit their home. Her thinking was that they might play together and forge a relationship that somehow could be of benefit to Rampo professionally. An invitation was extended which Watazumi accepted, though with the clear understanding that he would be well reimbursed for making the trip to Shizuoka. The visit was arranged and Watazumi and Rampo got along well enough, though Rampo did not become Watazumi’s student; he was already studying the music of Fukuda Rando as Fukuda’s deshi (apprentice), and this style of music was too sweet and romantic to suit Watazumi. Social visits continued however and ultimately a favorable relationship was formed between Watazumi and the Yokoyama family.

It is noteworthy that this relationship somehow facilitated Katsuya becoming Watazumi’s student when he was 24. Apparently it was not difficult for him to do so, though this was highly unusual since Katsuya and his father were both already students of Fukuda Rando and normally Watazumi would have instantly refused a request to study with him since they both already had a teacher. Perhaps Watazumi was persuaded by the payment Rampo made, and by the hospitality of the Yokoyama family.

Regarding Yokoyama Sensei’s multi-layered relationship with Watazumi, it is absolutely clear that Yokoyama thought of him as a musical genius and that many aspects of Yokoyama’s eventual playing style, as well as his sense of aesthetics and musical interpretation, were all heavily influenced by his association with Watazumi. At the same time however, Watazumi’s eccentric character and strong personality were difficult to warm up to. And, although Yokoyama apparently never spoke openly to anyone about any real discord between him and his teacher, it is perhaps instructive to note the he remained an active student of Watazumi for only about 10 years, and that during the last year or two his actual lessons had become quite infrequent.

Returning to Yokoyama’s education and career trajectory, after graduating from Shimizu Higashi High School in Shizuoka in 1952, Yokoyama took a company position at a plastics fabrication plant called Zeon which is still in existence. He worked the graveyard shift on the production line and apparently had not yet had any ambition of being a professional shakuhachi player – though he did tell one of his students later that during his days as a company man he was always very careful not to injure his hands. After several years of productive study with Fukuda and Watazumi however, his interest in the instrument and the music continued to grow, and in in 1958 or ‘59, after 6 years of working as a company man, he made the momentous decision to leave the relative security of having essentially a guaranteed job and income to devote himself to a full time professional career as a shakuhachi teacher and player. A primary motivation for leaping into such a risky and potentially unprofitable enterprise was his strong desire to keep the traditions of Watazumi Style Honkyoku and the Fukuda repertoire alive for one more generation of players. By this point he had already begun to work with students of his own, so that his aim to pass along the instrument and its music to others was already a concrete reality to him. To further this goal, he broadened his studies by enrolling as a student at the NHK Japanese Traditional Music Training Center where he augmented his background as a player by learning music theory and basics of composition. He completed his studies there in 1960.

From the beginning of his professional career, Yokoyama was interested in partnering with players from other backgrounds for the purpose of promoting shakuhachi music and continuing to see it develop as a contemporary musical form in Japan and around the world. In 1961, he formed the Tokyo Shakuhachi Trio (San-Jyuso-dan) with Miyata Kohachiro and Muraoka Minoru for the primary purpose of developing and promoting new music for the shakuhachi. Two years later, this aim was developed further when they went on to form the Nihon Ongaku Shudan (Ensemble Nipponia). Then the following year, in 1964, he founded the Shakuhachi Sanbon Kai (Group of Three Shakuhachi) with Kinko master Aoki Reibo and Tozan master Yamamoto Hozan. This clearly was a specific early effort to cross shakuhachi lineage lines in the service of promoting good shakuhachi teaching and performing throughout Japan. During these years he continued to work with his own students of course and as a group they comprised the Chikushin-kai Shakuhachi Guild which Yokoyama headed up for the duration of his career.

Something of a watershed event in Yokoyama’s early career came in November of 1967 when, at the age of 33, he was asked to perform the world premiere of “November Steps”. This very modern piece was composed by Takemitsu Toru for shakuhachi, biwa and orchestra, and was performed at Carnegie Hall by the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Seiji Ozawa. The performance was very successful and went a long way in establishing Yokoyama’s national reputation as a premiere player in Japan. Parenthetically, we should note that it may not have set well with Watazumi however, with whom Yokoyama still had a formal student relationship at the time, and who much preferred to see his young protégé devote his energy to mastering Honkyoku!

Over the next two decades, Yokoyama Sensei continued to teach and perform, and his success and reputation grew significantly. He became well known as a generous and devoted, but very exacting, teacher. He also became famous for the stupendous quality of his playing, perhaps as the definitive interpreter and performer of Watazumi’s renditions of a set of traditional Honkyoku. This specific repertoire, initially called DōKyoku as an acknowledgment of Watazumi Dōso’s founding contribution, was later simply called Koten (classical) Honkyoku. And as a distinct genre and shakuhachi lineage it became well known and appreciated, world-wide, under the fingertips of Yokoyama.

During the late 1970’s and into the 1980’s, Yokoyama began to take on more students from outside Japan who came to Tokyo to study with him. Over time, a desire began to build in him to see the shakuhachi shared and taught across lines of culture, nationality and specific lineage. This desire culminated in another seminal career move, the establishment of the Kenshukan in 1988. Formally called the Kokusai Shakuhachi Kenshukan (International Shakuhachi Institute), it was intended to be a manifestation of Yokoyama’s dream to have a residential facility where students could grow their own vegetables, prepare meals and maintain their own living space – somewhat like a monastery perhaps – while devoting themselves to the study of Watazumi-style Honkyoku and other shakuhachi repertoire. To that end, he leased a campus of empty school buildings in the small mountain town of Bisei near Okayama and began a schedule of recurring weekend workshops so that students of all nationalities could come to Japan to participate in affordable residential training.

This early effort was quite successful and after several years, another momentous step was taken. The decision was made that the Kenshukan would produce the first ever International Shakuhachi Festival, to be held at the Bisei training center in 1994. This was the long dreamed of event that brought together teachers, students and performers from virtually all of the different shakuhachi traditions active in Japan at that time. By all accounts the festival was a terrific success and in its wake the World Shakuhachi Society was created, with the first World Shakuhachi Festival being held in Boulder, Colorado in 1998. Since then, the World Festival has been and continues to be repeated on a regular basis in cities around the world. It continues to be well attended by many hundreds of students, teachers and performers of shakuhachi from many countries, and its continued popularity is a testament to Yokoyama’s vision about the value of sharing and integrating our diverse musical traditions.

Many of the other details of Yokoyama’s professional life are well known. Following the premiere of “November Steps” Yokoyama went on to perform the piece more than 200 times with orchestras in Europe and the United States. He also performed a variety of works with the NHK Symphony Orchestra throughout his career, as well as playing at the Tanglewood Music Festival and the Paris Festival. Other highlights of his career included being awarded the Geijustsu Sen-sho (Art Award) by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs in 1971, which was followed by the Geijutsu-sai Yushu-sho (Art Excellence Award) in 1972 and the Geijutsu-sai Tai-sho (Art Festival Grand Prize) in 1973. In 1991 he won the Ongaku no Tomo-sha Award, and in 2002 the government of Japan bestowed upon him one of its highest civilian honors, the Shiju Hosho (Purple Ribbon) for lifetime achievement.

Many of the other details of Yokoyama’s professional life are well known. Following the premiere of “November Steps” Yokoyama went on to perform the piece more than 200 times with orchestras in Europe and the United States. He also performed a variety of works with the NHK Symphony Orchestra throughout his career, as well as playing at the Tanglewood Music Festival and the Paris Festival. Other highlights of his career included being awarded the Geijustsu Sen-sho (Art Award) by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs in 1971, which was followed by the Geijutsu-sai Yushu-sho (Art Excellence Award) in 1972 and the Geijutsu-sai Tai-sho (Art Festival Grand Prize) in 1973. In 1991 he won the Ongaku no Tomo-sha Award, and in 2002 the government of Japan bestowed upon him one of its highest civilian honors, the Shiju Hosho (Purple Ribbon) for lifetime achievement.

On a personal level, Yokoyama is remembered for his warmth and generosity, his humor and gregariousness, and his commitment to his students. His life’s work was as much about sharing the shakuhachi across international and lineage-based lines as it was about mastering the instrument and playing to the delight and appreciation of audiences around the world. Musically, we have the legacy of his masterful and unbelievably beautiful recordings, as well as the memory (on the part of his direct students at least) of his constant injunction to “make a better sound!” This was clearly his own personal preoccupation right up to the end of his career and the reward to us is the legacy of his beautiful recordings as well as the way he shaped his senior students who have become living examples of the incredible sound Yokoyama was known and deeply appreciated for. Our collective debt of gratitude for what he started and for his myriad accomplishments is enormous.

If you would like to learn more about Yokoyama Sensei, a wonderful set of interviews is now available on YouTube, called “The Life and Legacy of Yokoyama Katsuya”, in which some of his most well-known disciples have the opportunity to reminisce about their own personal history with Yokoyama and share their insights and impressions of him as a teacher, performer and friend. These interviews were conducted and produced by one of the co-founders of KSK North America, Matheus Ferreira, and we are deeply grateful to Matheus for his work in making this resource available to us. As the first chapter in this series you can find the interview with Kakizakai Kaoru Sensei here: